No Maps for These Territories

On fictional cartography and the liquid geography of Arthur's Britain

Like most people I love fictional cartography out of all proportion to its actual importance in the universe. I can and will never have enough fictional maps ever. They give me much the same pleasure novels do but in concentrated form—a fictional map is like a novel that has somehow been dehydrated and pressed flat so you can eat it in one infinitely rich and delicious bite.

Like fruit leather. But moreso.

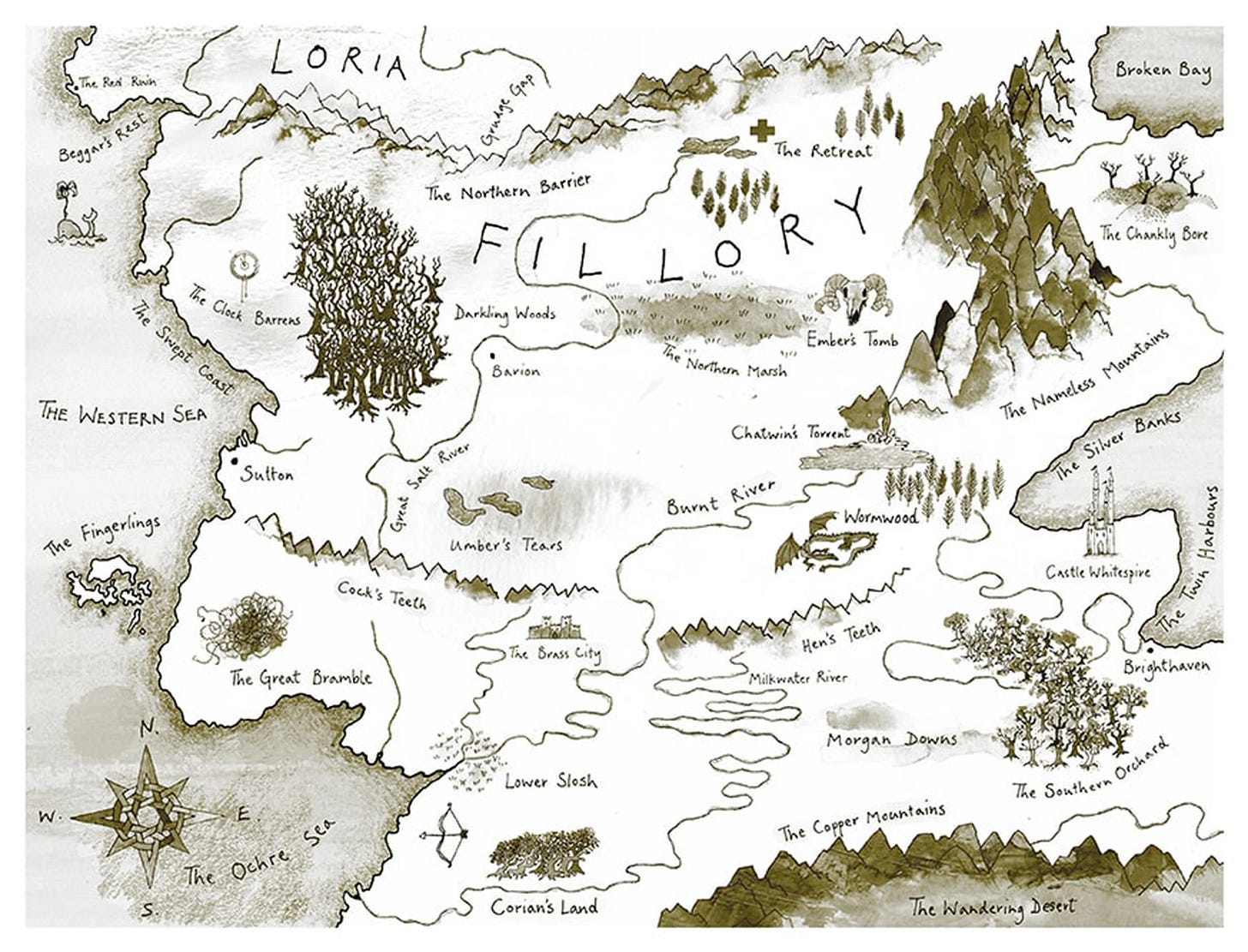

When The Magicians was published I desperately wanted to have a map in it; actually what I really wanted was, like Tolkien, to have a map in it that was drawn by me. But I tried to draw one and, as usually happens when I try to emulate Tolkien in any way, I failed miserably. So we hired a professional to draw it.

Anyway, I did get a map.

When it came time to design the interior of The Bright Sword, my editor told me—before I even asked—that that was then, ten years had passed, times had changed in the publishing world, and like a reawakened Austin Powers I would have to adjust my expectations because there was no money in the budget anymore to do endpaper maps like we had in The Magicians.

I should’ve been disappointed, but in fact I was a little relieved, because I’m actually not sure Arthur’s Britain is mappable.

That’s not true. I have written an untruth. Some versions of Arthur’s story are definitely historically grounded enough and geographically rational enough to be mapped, viz. Bernard Cornwell’s Warlord Chronicles, or Mary Stewart’s Arthurian saga. But you won’t find a lot of maps floating around of, say, the Morte d’Arthur, and I think the main reason is that in the classical Arthur stories Britain is, by convention, absurdly elastic and incoherent. Knights are constantly riding unspecified distances for arbitrary amounts of time, and mentioning places but giving them no fixed location in space and then never mentioning them again. You would have to draw the map on silly putty.

As a result the geopolitics of Arthur’s realm lack any real historical grit or texture. Arthur is often represented as having conquered Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Iceland, France and Rome, among other places, claims clearly made by someone with a limited familiarity with cartography. And just try to figure out where Camelot is! Many have tried. It’s not possible. Well, Malory said it was in Winchester, but he was wrong. Even Chrétien de Troyes, who invented Camelot in the 12th century in a throwaway line in Lancelot, didn’t know where Camelot was. Or Avalon, Lyonesse, Sorelois, Camelyard, Corbenic … these locations can’t and don’t want to be fixed in rational space. When I wrote The Bright Sword I worked off a kind of mashup of this and this, but often I just went my own way.

It’s possible that this is how Arthur would have experienced his own kingdom. He wouldn’t have had a map of it, because there were no maps of Britain in the 6th century. It would have been just a shifting mental network of roads and rivers, junctions and fords and landmarks and ephemeral political boundaries.

But Tolkien thought this sort of thing was just shoddy worldbuilding (maybe this is one reason he gave up on his own Arthurian epic, “The Fall of Arthur.”) He considered maps to be an essential part of fantasy writing—he actually used his maps to calculate how far his characters could realistically travel on a given day, by a given mode of transport, and made sure the story stuck to it. It’s one of the things that makes his world seems so real and solid. (I suspect that George R.R. Martin does the same thing.)

But Arthur’s world isn’t solid. When you’re out on a quest, deep in the forest, far from home, geography becomes liquid. It doesn’t matter where you’re going, you’ll get there when God and the adventure permit it and not a moment sooner.

Epilogue: I did in fact start sketching a map of Arthur’s Britain, purely for my own private use, but the project immediately became unworkable. Here it is, please ignore it:

I love fantasy maps too but I think they can't be trusted. In worlds where everything else is strange, and is narrated by particular characters who make histories in circumstances not of their choosing, the idea that the reader can know for sure how long it will take a laden hobbit to reach Illisifiliorn is not credible. It's a bit like the Bible though - how we start with the grand and cosmic and utterly sure knowledge that everything was made in seven days and then immediately Cain kills Abel and probably doesn't even know why. We don't really know why. My favourite map though is the Half-Continent. The novel concerns such a small fraction of this world, it makes the uncertainty of everything much greater without diminishing its urgency.

There's two things this makes me think of: one, David Lowery's recent Arthurian adaptation The Green Knight, which has that sense of taking place in a delightfully flexible nowhere that you describe (I wonder if that's one reason the landscape around Camelot early in the movie is so blank?), and two, Nicola Griffith's Hild and Menewood, which are set in seventh-century Britain. They do have maps for the reader's edification, but it's clear that the characters aren't using maps--they're using their memories, their understanding of the landscape, and their knowledge of relationships to carry an internal sense of a constantly shifting geography.

It's the kind of effect I'd love to be able to achieve.